Vaishakh Krushna 5,Kaliyug Varsha 5114

|

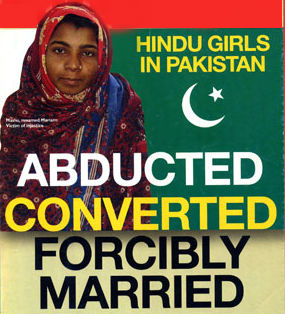

On March 26, 19-year-old Rinkle Kumari, from a village in Sindh, told Chief Justice of Pakistan Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry that she had been abducted by a man called Naveed Shah, and pleaded with the highest court to let her return to her mother. It was a brave plea. Hindu women in Pakistan are routinely kidnapped and then forced to convert if they want the respectability of marriage. They are helpless, as they have neither the numbers nor the political clout to protect themselves. As Rinkle left the court, she screamed before journalists, accusing her captors of forcible conversion, before she was hustled away by the police.

The case grabbed headlines, generated impassioned editorials, and highlighted the cause of a persecuted community, the 3.5 million Hindus in Pakistan. It angered liberals in Pakistan and caused the Dawnnewspaper to take a strong position on persecution of minorities.

But Rinkle had dared to raise her voice, and there would be a price to pay. Her parents in Ghotki village were threatened, her 70-year-old grandfather was shot at, gun-toting goons roamed outside her house. When she returned to the Pakistan Supreme Court on April 18, she meekly said she had converted to Islam. At a packed media briefing in Islamabad’s Press Club, with Shah by her side, the spunk in her snuffed out, she would only say she wants to become an "obedient" wife.

According to police records, each month, an average of 25 girls meet Rinkle’s fate in Sindh alone, home to 90 per cent of the Hindus living in Pakistan. Young Hindu girls are ‘marked’, abducted, raped, and forcibly converted. Discrimination, extortion threats, killings and religious persecution are driving the remaining Hindus out of Pakistan. They had chosen to stay back after Partition; six decades later, they are no longer welcome.

In India, they are facing a shock worse than catastrophe-betrayal. The Government of India refuses to recognise them as refugees and is unmoved by their plight. In its reply to activist S.C. Agrawal’s RTI query on November 1, 2011, on the status of Pakistani Hindu refugees, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) claimed it was an "internal matter” of Pakistan. In the same reply, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) admitted that it could not say how many Pakistani Hindus had emigrated.

According to Delhi’s Foreigners Regional Registration Office (FRRO), there has been a rapid increase in the number of Hindus coming from Pakistan. Till mid-2011, it used to be around eight-ten families a month. But in the past 10 months, an estimated 400 families have come. They are settling down all over India, in Rajasthan, Punjab and Gujarat. A trickle has become a stream. Hindus, who accounted for 15 per cent of Pakistan’s population in 1947, now constitute a mere 2 per cent of its 170 million population. Many have migrated, others have been killed, and yet others forced to convert to survive. In some cases, the dead have even been denied a proper cremation.

Ask Meher Chand, 55. He arrived in Delhi on January 21, 2011, with a delegation of Pakistani Hindus, carrying 135 plastic jars, aboard the Samjhauta Express. The jars contained the ashes of Hindus who had died in Pakistan, some of them way back in the 1950s, and stored in Karachi’s Hindu Cremation Ground. The remains were finally allowed their final journey, to be scattered in the Ganga.

Chand did not return to Pakistan. He joined a group of 200-odd Pakistani Hindus settled in Jahangirpuri in Delhi. His voice chokes as he talks about what he faced in Karachi. "My wife died of cancer in 2009, leaving two daughters behind. One morning, soon after my wife’s death, I found my younger daughter, 16 at that time, missing. When I made inquiries, I was told that she had eloped with a much older man, known to be a goon. She had converted to Islam overnight. I was allowed to meet her after intervention by some elders. She cried and hugged me without saying a word. I never believed she eloped. The man had been eyeing my daughters. I managed to marry the older one in time. This one was just a child," he trails off. "I wish I had the courage to fight for my daughter. The kidnappers had private armies and threatened me. Even the local police did not pay heed. They mocked me on the streets," says Chand.

The Jahangirpuri camp mostly has people who have come from Sindh, Karachi and Hyderabad. Most of the other refugees from the region are concentrated in Rajasthan and Gujarat. Some have been here since the 1990s and have still not got citizenship and accompanying conveniences like a ration card, driving licence, gas connection, right to buy property and even travelling to another part of the country, other than the one place their visa permits.

|

"There are thousands like me who want to come and settle in India but are constrained by the border,” says Chand, sitting in a one-room tenement he shares with three other refugees. Chand was a hakim (medical practitioner) in Karachi. Even though he has acquired a small clientele within the camp and nearby, his income is not even one-fourth of what it used to be.

Others in his camp feel Chand has spoken more than he ought to. They chide him, saying he will face problems with the Pakistan High Commission. "Till we get citizenship of India, we remain Pakistanis, and have to go to the high commission again and again. Earlier, they used to renew our passport for five years, now they are doing it on an annual basis. They ask us uncomfortable questions,” says a camp resident.

There are many more like Chand, waiting to flee Pakistan for the safety of their daughters. Sitting in a well-furnished drawing room of his house in Ghotki, Sindh, 52-year-old Kishore Kumar is a worried man. Wealth has not provided him any security. Owner of three textile-ginning factories, and father of two daughters and a son, he is preparing to leave Pakistan. "It is hard to leave your place of birth, the place where four generations have been born. But we have to move now as things have become critical. I love my motherland but I am shifting to India for the future of my children,” he tells India Today.

Kumar expresses concern about his two college-going daughters. "You can’t imagine what it means to be the father of two young girls in a land where minorities are treated like third-class citizens. I receive extortion calls from people for hefty sums to ensure my family is not touched, especially my daughters," he says.

He is waiting for his visa, which has increasingly become difficult to get. It took 38-year-old Dr Ashok Kumar Karmani three years to get a visa for himself and his family, enabling passage from Mir Khas in Sindh to Ahmedabad in February 2012.

After the 2009 Mumbai terror attack, India put curbs on visas from Pakistan. Only one out of five visa applications gets cleared. "If visa rules are eased, the majority of Hindus in Sindh would shift to India,” says Karmani.

Son of a businessman and a medical graduate from Liaquat Medical College in Karachi, Karmani was living in a huge bungalow as part of a joint family. Now he hopes that he, his wife Ramila, a science graduate, and their two children get a long-term visa soon,and permanent citizenship after they complete seven years in India. The family is worried about those left behind. "There are dozens of cases in Sindh where Hindus have become targets of kidnappings and forcible conversions. It was time to say goodbye," says Karmani.

Indeed, the prejudice against Hindus runs deep. Lahore High Court Chief Justice Khawaja Muhammad Sharif is reported to have said that Hindus were responsible for financing acts of terrorism in Pakistan. A March 18 editorial in Dawn pulled him up for it: "It may well have been a slip of the tongue by Mr Sharif, who might have mistakenly said ‘Hindu’ instead of ‘India’- nevertheless, it was a tasteless remark to say the least.”

There are other liberal voices. Dr Azra Fazal Pechuho, member of the National Assembly and elder sister of Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari, told India Today that she believes girls like Rinkle Kumari are being forcibly converted. "It is true that Hindu girls are being forcibly kept in madrassas in Sindh and forced to marry Muslims. We have to take steps to end this practice, including legislation,” she says.

Among the latest to flee Pakistan is a group of 145 Hindus who arrived in Delhi in December 2011 on a pilgrimage (jattha) visa. They managed to extend their visa and are looking forward to being accepted byIndia as citizens. Staying in makeshift tents at Majnu ka Tilla in north Delhi, Savitri Devi, 32, gave birth to her daughter in the camp two months ago. "When policemen come to remind us we have to leave, I show them my daughter Bharti and tell them to at least accept her as she was born on Indian soil," she says, nursing the infant with her older daughter Rani, 3, sitting alongside.

There is no way that they want to return to Pakistan. "I have been trying for a visa for the past five years and got it only now, that too only as part of the jattha,” says Krishan Lal, 30, as his wife Rukmani makes chapattis nearby. His three children run around in the camp barefoot, playing with other children. "Hindus are like fish out of water in Pakistan. They all want to come to India, hoping to put an end to their miseries-but it is a different story here altogether,” he adds.

Krishanlal Bhatar, 54, who came with his family from Mirpurkhas district of Sindh to Ahmedabad in 2009, says with folded hands, "We don’t want anything from this country, only security. We shall remain loyal to India forever and die in this land only.” Tears roll down his cheek as he recalls his life as a grocery shop owner in Pakistan. His is the all-too-familiar story of a daughter, Jaymala, 22, kidnapped, converted and married off to a Muslim farm labourer.

Bhatar and his family went pillar to post to get her custody. Local Pakistan Peoples Party politicians whom he approached were either hand in glove with the group that had kidnapped the girl or too scared. Bhatar managed to file a case and also went to the court. On the day of the final hearing in the court, over three dozen Muslim boys gathered, many of them rifles in hand. A trembling Jaymala was brought before him and his wife. She didn’t even look at them and just told the woman judge, "I don’t know them.”

Pujari Lal, 31, came from Kohat near Peshawar in 1999 and settled in Khanna, Punjab. He fled after his teenaged sister was kidnapped and raped. He does not feel comfortable talking about it but dwells in detail on the problems in Khanna. There are around 1,200 Hindus and Sikhs settled in Khanna. "It has been 13 years but I still don’t have Indian citizenship. My papers have come back a dozen times. They want proof of my parents’ date of birth and birthplace. My father is dead; my mother is with me but we do not have all the papers," he says.

Lal sells tomatoes and chillies in the crowded wholesale vegetable market in Khanna. Pakistani refugees run the mandi here. The relatively better-off ones have bigger shops, and can afford to do the running around between the Government offices, the Pakistan High Commission and FRRO. They are thrilled that one among them, Data Ram, 33, recently got a no-objection certificate from both the Pakistan High Commission and the home ministry, making him eligible for citizenship. Now he needs Rs 6,000 each for his five family members as passport forteiture fee and is in the process of "arranging the money". Having finished high school, Ram is one of the most educated persons there. He says he had kept all his papers meticulously, making it easier for him to get citizenship. They all come to Ram for advice. He tells Lala Madan Lal that since he was born in 1946, he is eligible for citizenship according to the Indian Citizenship Act.

In the Al Kausar settlement of Hindu Pakistanis in Jodhpur, Tulsiram talks about the problems in getting a visa from the Indian High Commission in Islamabad. From Tharparkar district in Sindh, where most emigrants in the camp came from, it is a seven-day journey to Islamabad, which not many can afford. "The minimum cost for such a journey is Rs 30,000,” says Tulsiram, who was a scribe in Sindh. He calls it a policy of discouragement by the Indian ministries of home and external affairs.

In another camp amid the sandstone quarries on the outskirts of Jodhpur, Jamuna Devi, 40, talks about lack of amenities at the camp. "When our children fall ill, Government hospitals refuse to give us medicines, saying we are Pakistanis,” she says.

Rana Ram, 32, personifies the problems on both sides of the border. He came to Jodhpur in 2008 with his two children after his wife Samdha Ben was kidnapped, raped and converted by religious fundamentalists in Rahim Yar Khan. "I entreated them to return my wife. They just laughed,” he says. In Jodhpur, the community members got him married again so that his children could be looked after. His second wife died of malaria within two months.

Since they are not a votebank, only a handful of politicians have taken up the cause of Pakistani Hindus and Sikhs. Avinash Rai Khanna, a BJP Rajya Sabha MP, keeps raising questions about their plight in the Upper House. It was in reply to a question raised by him on persecution of Hindus in Pakistan that Minister of State (MoS) in mea E. Ahamed said on March 22: "The Government has taken up the matter with the government of Pakistan. It has stated that it looked after the welfare of all its citizens, particularly the minority community.” A secular India’s mea accepts Pakistan’s claims at face value. They claim that since India does not endorse any religion, it cannot be seen as speaking for Hindus in Pakistan.

Data collected by India Today defies Pakistan’s claim. More than 90 families migrated to India in 2010, 145 in 2011 while 54 Hindu families have already migrated to India since January 2012. Since 2010, as documents show, 24 Hindu families migrated toNepal while 12 families chose to live in Sri Lanka after fleeing Pakistan. In February itself, 30 Hindus comprising five families left Thul, a small town in Jacobabad district, for India.

In reply to another question by the MP on March 28, MoS in MHA M. Ramachandran said that they had received 148 applications for citizenship of Pakistani Hindus from Punjab state from 2009 to 2011. Only 16 applications were accepted for citizenship; 119 are pending for want of documents and 13 were rejected.

Amid the cold figures of rejection are the scars left on the psyche of refugees. Lala Madan Lal, 66, of Khanna, recently read Toba Tek Singh, a short story by Saadat Hasan Manto in Urdu, and can’t stop talking about it. "Like Bishan Singh in the story, we will all die in no man’s land as people with no land to call their own," he rues.

Source : Yahoo