Mizoram erupted in celebrations Saturday (December 2) over the Election Commission (EC) bowing down to pressure from everyone in the state–political parties, church bodies and civil society organsiations–to defer the counting of votes scheduled for Sunday (December 3).

All stake-holders in Mizoram, which is predominantly Christian, had demanded that the counting of votes for the Assembly elections–voting was held in the state on November 7–should not be held on Sunday since the day is reserved “exclusively for prayers”.

After receiving numerous petitions from various organisations and all political parties and also deputations from prominent civil society organisations over the past few weeks, the EC accepted the demand. The counting of votes in the state will now take place Monday (December 4).

The Mizoram Kohram Hruaitu Committee (the apex body of various Christian denominations) which had spearheaded the demand, said: “We regard it as the intervention of God that our prayers and wishes have been accepted through the ECI”.

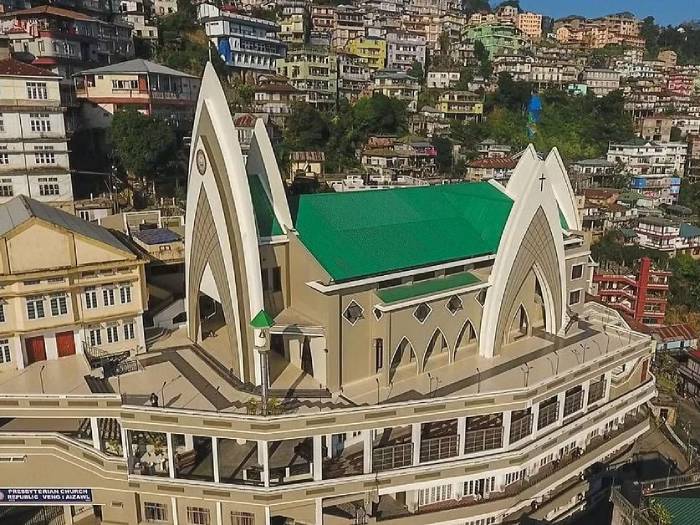

Public sentiments in Mizoram, which proudly calls itself a ‘Christian state’, had been building up over the past few weeks on this issue. Friday (December 1) saw a huge protest rally in state capital Aizawl.

A two-point resolution condemning the decision to hold the counting of votes on a Sunday and urging the EC to defer the exercise to a weekday was passed at the rally that was attended by representatives of all political parties and church bodies.

Lalhmachhuana, the chairman of the NGO Coordination Committee (NGOCC)–the representative body of all influential civil society organisations in the state–explained to Swarajya: “Sunday is a holy day for all Mizo Christians. The day holds immense religious significance for Christians as it is a day dedicated to the worship of God, making it a pivotal and cherished occasion”.

Lalhmachhuana, who is also the president of the powerful Central Young Mizo Association (CYMA)–a body which has almost all Mizo young men and women as its members and has branches all over the state–said that Mizos go to church to pray and desist from all other work on the day.

“Sundays are Sabbath, a day exclusively for praying and engaging in religious work. It is ordained that no work be done on this day. So counting of votes cannot also be done on a Sunday,” said Mizoram Upa Pawl (MUP) vice president Lalbiakmawia Khiangte. MUP is another powerful body of elders of the Mizo community.

The EC’s acceptance of the demand to defer counting from Sunday was hailed by everyone, including politicians and church leaders. They hailed the EC displaying sensitivity to the religious sentiments of ‘the people of a Christian state’.

No criticism of the demand

What’s noteworthy is that the demand did not elicit criticism from any quarter outside Mizoram. No political party or civil society organisation, no agnostic, atheist or rationalist or ‘secular’ group opposed or criticised the irrational demand of the Mizos.

Irrational because counting of votes is not a community exercise that would have required a huge number of Mizos to work in counting centres instead of going to Church. At most, only a couple of hundred government employees would have been required for the job (of counting).

Also, many Christians in other parts of the world don’t, at least not regularly, follow the Sabbath and that does not make them any less Christian.

Very few Christians follow Sabbath religiously and desist from doing any work on Sundays. Apart from going to Church, Mizo Chrisitians can be seen doing household work and even office work on Sundays.

Counting of votes–with EVMs in use, is not really physical counting of ballots any more, but that’s beside the point–for a small state like Mizoram with 40 constituencies and a total electorate of about 8.5 lakh requires the involvement of a small number of people.

December 3 would not have been the first time that government employees of Mizoram would have been asked to work on a Sunday.

Government employees in Mizoram have worked on Sundays during emergencies, or when important work needed to be done. For instance, employees of the finance department work on Sundays before the budget is presented to the state Assembly.

Government employees work on Sundays to clear pending bills and do other urgent work before the financial year ends on March 31. They have worked, and will continue to do so, on Sundays if and when important and urgent ‘official’ tasks require their presence in their offices or other places.

The demand for deferring counting because the day happens to be a Sunday is can also be seen as an attempt to assert Mizoram’s ‘Christian identity’ and set it apart from the rest of the country.

The EC should have rejected the demand since it now opens the floodgates for similar demands being raised by not only the other Chrisitian-majority states of the Northeast (Meghalaya and Nagaland), but also by other religious communities.

Muslims, for instance, will now be justified in demanding that no work, including conducting Assembly or other polls, be held on Fridays in the Muslim-majority Kashmir Valley or in Lakshadweep.

But what if Hindus were to raise similar demands?

What if, for instance, Shaivites demand that polling or counting of votes, or other important official work, should not be held on Mondays?

What if Hindus, especially those who worship Hanuman, demand that polling or counting of votes should not be held on Mangalvar (which translates into ‘auspicious’ day)?

What if, for instance, people of Odisha–most are devotees of Bhagwan Jagannath (a representation of Bhagwan Bishnu)–now demand that no important official business should be conducted on Vrihaspativar (Thursday) since that day is dedicated to Vishnu?

Hindu individuals and organisations, if they were to voice such a demand, would have been termed ‘regressive’, ‘communal’ and worse.

Such a demand—if ever made—by Hindus would likely face nationwide ridicule, with campaigns mocking the community and shaming those advocating for it. However, it seems acceptable for other communities to make such demands.

This situation serves as a stark reminder of the hypocrisy prevalent in many Indians.

Postscript: Apart from Christian-majority Mizoram calling itself a ‘Christian state’, Nagas also call their state a ‘Christian state’. ‘Nagaland for Christ’ is an assertion of sorts that is heard, and even emblazoned in walls, across Nagaland.

Christians, especially those belonging to the Khasi and Jaintia communities, have started referring to Meghalaya as a ‘Chrisitian state’.

The assertions by Chritisians of these three states that their respective states are ‘Chrisitian states goes completely uncontested and does not attract even mild censure or criticism.

Source: swarajyamag.com