By Sandeep Balakrishna

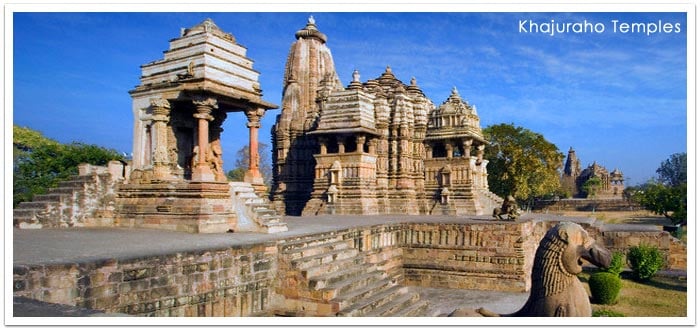

The first and the most common refrain in the defence of the perverse paintings of Hindu Gods, Goddesses, symbols and icons of the dead barefoot painter M.F. Hussain is how sex and nudity were “very much a part of ancient/medieval Indian art.” This refrain is then followed up with liberal citations of nude sculptures of Hindu Gods and Goddesses in medieval Hindu temples, and in erotic (mainly) Sanskrit prose and poetry. Of course, the much-abused example of Khajuraho is brandished for good measure.

And then the defence stops at that and typically moves on to bashing everybody who’s offended by Hussain’s paintings as communal and right wing Hindu fascists and the rest. That narrative has been convincingly debunked over the years – the most famous one being by Arun Shourie – and stands totally discredited now as it should be.

However, it does help to explore a bit about the underlying theme behind said nudity and sexuality in ancient and medieval Indian sculpture and the Arts. Or in other words, to try and understand the role and place of sex in the Hindu Arts in today’s context.

The fundamental place to begin this exploration is to honestly, dispassionately and detachedly examine our own attitudes towards sex. With this same honestly and detachment, it is not inaccurate to say that these attitudes are shaped by the Christian (more accurately, Abrahamic) orientation towards sex: as sin, and therefore filthy and dirty.

And this is reflected everywhere from no-holds-barred pornography (print and digital) to the more subtle mainstream publications. Mainstream publications must by their very nature exercise strenuous balancing so as to not degenerate into pornography, and so, although the messaging is the same, the verbiage differs: we read terms like “carnal craving,” “dirty delight,” “sinful sensuality,” and so on. It can also be argued that we certainly don’t interpret this verbiage literally but what subconsciously propels us to associate sex with those specific words? Any guesses which dominant world religion gifted us this association?

It is both interesting and rewarding to trace the rough timeline when Khajuraho attained renown as an erotic-art (sic) tourist destination. A safe estimate would be around the time when the West became “sexually liberated.” In other words, when Western women vociferously asserted their sexuality and demanded equal rights to have sex without marriage being a precondition.

As is the case in most other fields, a few years later, India followed suit and suddenly rediscovered the abundant sensuality lying in its own backyard: from Kamasutra to Khajuraho. A significant number of scholars from all over the world embarked on a single-minded pursuit of digging into the Hindu past to unearth mountains of eroticism in prose, verse, music, mythology, drama, painting, and folk.

Which brings us to the question: why then was sex so ubiquitous in Hindu art? And why do large numbers of Hindus find the sex as depicted by today’s Indian artists so offensive? At the risk of broad-brushing, two other questions come to mind: why have no artists, comparable to the unnamed and unknown medieval geniuses, emerged out of post-Independence India in significant numbers? Equally, why don’t we have temple-architecture and sculpture even bordering on the scale and eminence of India’s past in the contemporary period?

Which brings us to the question: why then was sex so ubiquitous in Hindu art? And why do large numbers of Hindus find the sex as depicted by today’s Indian artists so offensive? At the risk of broad-brushing, two other questions come to mind: why have no artists, comparable to the unnamed and unknown medieval geniuses, emerged out of post-Independence India in significant numbers? Equally, why don’t we have temple-architecture and sculpture even bordering on the scale and eminence of India’s past in the contemporary period?

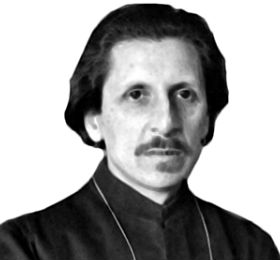

At length, we can now turn to Ananda Coomaraswamy, the seminal and prolific author, musicologist, multifaceted scholar and art critic and connoisseur. In his masterly and comprehensive Aims and methods of Indian Art, he says:

By many students, the sex symbolism of some Indian religious art is misconceived: but to those who comprehend the true spirit of Indian thought, this symbolism drawn from the deepest emotional experiences is proof of the power and truth alike of the religion and the art. India draws no distinction between sacred and profane love. All love is a divine mystery; it is the recognition of Unity. Indeed, the whole distinction of sacred and profane is for India meaningless….[Emphasis added]

This is the answer as to why millions of Indians are offended by M.F. Hussain’s perverse masterpieces, but regard as sacred the nudity/eroticism depicted in Hindu temples. Popular consensus in public discourse claims that it is the nudity that offends these puritan Hindu fascists whose minds have been hijacked by the Hindutva folks who in turn have hijacked the true Hinduism which celebrated sexual openness. Here is Monier Williams, quoted by Coomaraswamy, on how sex is regarded in Indian thought:

…in India, the relationship between the sexes is regarded as a sacred mystery, and is never held to be suggestive of improper or indecent ideas. [Emphasis added]

The last line echoes what I mentioned earlier: that before India’s cultural consciousness was Abrahamized and later Victorianized, verbiage like “carnal craving” and “sinful sensuality” were alien, and therefore incomprehensible to a culture that celebrated all of life as sacred.

Ananda Coomaraswamy then quips in the same essay that as much could hardly be said for Europe. The entire passage is truly worth its weight in gold.

…the possbility of such symbolism lies…in the acceptance of all life as [sacred], no part as profane. In such an idealisation of life itself lies the strength of Hinduism, and in its absence the weakness of modern Christianity. The latter is puritanical; it has no concern with art or agriculture, craft or sex or science. The natural result is that these are secularised, and that men concerned with these vital sides of life must either preserve their life and . religion apart in separate water-tight compartments, or let religion go. The Church cannot . complain of the indifference of men to religion when she herself has cut off from religion, and delimited as ‘profane’, the physical and mental activities and delights of life itself. [Emphasis added]

As experience testifies, life is a unified whole broken into parts only by the mind. Indian thought assigns only a secondary significance to Mind, which is why philosophy (embodied in Vedanta) and spirituality, and not psychology, left its lasting roots in India.

The story of Hiranyakashipu and Prahlada is a classic and timeless illustration of this wholesomeness. Although a demon/evil incarnate, Hiranyakashipu is consumed with lifelong hatred and for Vishnu who he sees as his only foe who he must destroy at any cost. Prahlada, his son, is the opposite: he is a steadfast devotee of Vishnu. Father and son are engaged in all-consuming, unwavering penance for the same person but while in the former it becomes hatred, in the latter it manifests itself as devotion. Therefore while Hiranyakashyipu searches in vain for his foe in all the worlds and builds his frustration at the inability to locate him, his son is at peace in the confident knowledge that his father’s sworn enemy is within his own heart. And therefore when the time approaches, Prahlada is able to summon the object of his devotion even from within the confines of a pillar.

This lofty philosophy is what underlies almost every facet of Hindu life including its temples, sculptures and the rest.

Ananda Coomaraswamy then quickly and effectively evaluates modern (Western) art in his own time. If memory serves me right, the period under his consideration is the early 1900s.

Passing through the great galleries of modern art, nothing is more impressive than the fact that none of it is religious. I do not merely mean that there are no Madonnas and no crucifixes; but that there is no evidence of any union of artistic with the religious sense… Such art appears therefore, let us not say childish, for children are wiser, but empty, because of its lack of a true metaphysic. Of this the cries of realism and ‘art for art’s sake’ are evidence enough. A too confident appeal to the so-called facts of nature is to the Indian mind conclusive evidence of superficiality of thought. For the artist above all must be true, for the first essential of true art is not imitation, but imagination. [Emphasis added]

Indeed, this imagination animates all great works of Hindu art. It would be foolish on my part to add anything more on sex symbolism in Indina art after Coomaraswamy’s exposition. So I’ll depart with an elevating sequence from the 1997 Telugu film, Annamayya based on the life of the 15th Century saint-poet-musician, Annamacharya.

In this overtly commercial but a well-made movie, Annamacharya is shown to be an ardent sensualist in his early youth. To make him see the futility of his overt sensuality, Vishnu descends to the earth in human form and takes him to a temple. Whereupon, Annamacharya points to him a host of erotic sculptures on its walls, and asks Vishnu how and what he feels about them. In a sweetness of language and expression that is possible only in Telugu, Vishnu replies: “in those sculptures I behold the unseen parents of the entire inert and sentient Cosmos engaged in the Yagna of creation.”

Source: indiafacts