Ashwin Shuddha Dashami

On the evening of Saturday, September 13, a series of bomb blasts ripped through the capital. The blasts took place in the most popular and crowded shopping centres, killing 25 and injuring 200.

Six days later, the Delhi Police conducted a raid on a flat in Zakir Nagar, an area where many students of nearby Jamia Millia Islamia stay. Two persons inside the flat were killed as was a highly decorated officer who led the raid.

One occupant, Mohammed Saif, was arrested. The police announced that one of those killed was Atif, the mastermind behind the blasts. Two members of the terror module managed to escape.

The caretaker of the Zakir Nagar flat, Abdul Rehman, was the key to three more arrests on September 21, three educated young men: Zia-ur Rehman, Saquib Nisar and Mohammed Shakeel.

The three were charged with being a major operational arm of the Indian Mujahideen and with planting bombs, not just in Delhi but in Ahmedabad and Jaipur as well, sites of earlier serial bombings.

Rehman, Nisar and Shakeel were paraded before the media and then whisked away for a police interrogation. India Today’s Mihir Srivastava managed to talk to the trio exclusively. Here is his first person account.

They look like earnest young students, clean-shaven, educated, well-dressed, soft-spoken, almost the boys next door. Saquib Nisar, Zia-ur Rehman and Shakeel are all in their early 20s.

After they were picked by the police from Zakir Nagar, a common friend of the trio facilitated two meetings with them, at the Zakir Nagar police station and later during the press conference called by the South District police to announce their arrest.

These meetings resulted in a frank discussion, scary in terms of the twisted ideology as well as the hatred and desire for revenge that underlines everything they say. More alarming is the matter-of-fact way in which they describe their acts of horrific terror and widespread death and destruction.

What is more frightening is that they could be young men you meet in a local Barista café or see working on their laptops at a cyber café. Up close and personal, they turn into something malevolent, walking bombs who perform their act of mass slaughter in the name of Allah and without the slightest suggestion of remorse.

Behind their endearing looks hides an enduring sense of being wronged. This has clouded every faculty of their intellect and reduced them to willing instruments of the invisible puppeteers of terror.

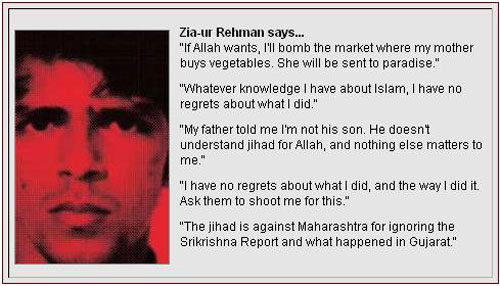

Zia-ur Rehman, 24

A third year student at Jamia Millia Islamia, accused of planting bombs at Connaught Place and Ahmedabad and providing logistical support.

|

Zia-ur Rehman is sitting with his father, who had also been arrested for forging the rent documents of L-18, Batla House, the infamous flat where the terror module led by Atif lived. The thick chain attached to Rehman’s hand is a complete contrast to his frail frame.

He is small, thin, bony, fair, not more then 5’5" tall, and wears an expression of utter disgust on his face, suspicion too, but at the same time, does not seem to care the least about his fate or the fact that he committed mass murder just a week earlier.

His sharp, wide eyes are partially open; hooded, impossible to penetrate. He wears black trousers and an oversized, light shirt that hangs below his waist. His tone is abrasive and he has an unfriendly vibe about him. Yet, when he starts speaking, cold chills run down my spine.

"You planted the bombs?" I ask. "Yes," he says, forcing his eyes open. "Your friend, Nisar, feels that he was taken for a ride by Atif in the name of Allah," I introspect as he leans forward, as if not wanting his family to hear his words.

"Whatever knowledge I have about Islam and what I understand about how things work in this world, I have no regrets about what I did," he whispers. "So, if you had not got arrested, you would have gone on to plant the bombs at Nehru Place as per the plan?" "Yes," he replies without hesitation.

His small frame becomes rigid, the nerves on his frail forearm tense. "It is a jihad, it’s a war," he declares. This is followed by my next query—"Who is your enemy?" Rehman parrots without emotion, "This is jihad for Allah, only the privileged get to do it." It is only then that I ask him, "But who is your jihad for Allah against?" He tries to find words to describe his enemy.

His concept of an adversary seems amorphously lost in the deep-rooted sense of insult he feels at belonging to a certain religion. He says, hesitantly, "It is against Maharashtra for ignoring the Srikrishna Report; it is against what happened in Gujarat."

But how would killing people, say in Karol Bagh in Delhi, help target those responsible for say Maharashtra or Gujarat? The question agitates him, his temper flares. Raising his hand to stop me speaking, he says: "I have no regrets about what I did, and the way I did it. Ask them to shoot me for this," he asserts, his thin lips clamped tight.

At this point, his thin innocuous body looks ominous, dangerous, like a living bomb. "How many like you are ready to kill in the name of jihad?" "I know only Shakeel and Nisar, Atif is dead, a few more," he replies. "There will be thousands willing to join the jihad," he adds as an afterthought. And what about the Indian Mujahideen? "I know only of Atif."

Prodding further, I ask, "When you went to Ahmedabad, didn’t it bother you who paid for your travel?" He responds, "I knew there was someone very generous to us, he was a lover of Allah and was supporting us in all possible ways."

"Did your parents know about it?" "Now they do," is the blunt reply. "My father is upset with me. He told me that I am not his son. He does not understand jihad for Allah, and nothing else matters to me."

Would he plant a bomb in the same market where his mother buys vegetables? He remains quiet again, turning the idea in his mind. "If Allah wants, I will do so. Meri valida ko jannat naseeb hogi (my mother will be sent to paradise)," he replies.

He looks almost as if under a spell, unthinking, unfeeling, a machine engineered to kill. All in the name of Allah. What’s even more frightening is that many more like him could be out there.

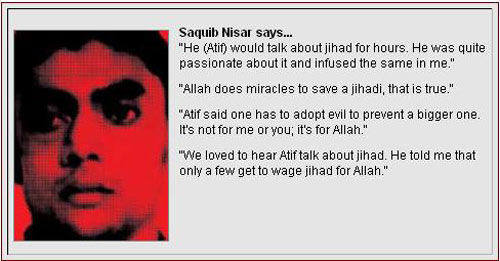

Saquib Nisar, 23

A Jamia Millia Islamia graduate, now pursuing a management course from Sikkim Manipal University, accused of being part of the Ghaffar Market reconnaissance team.

Saquib Nisar is handcuffed, a policeman at his side. He is slim, fair with good looks, large, expressive eyes; his face looks tired for lack of sleep. He wears well-fitting blue jeans, a red and white bold striped shirt hangs loosely on his slim frame. He looks eager to talk despite having undergone hours of extensive police interrogation. One gets the impression that he belongs to a family of a certain level of affluence.

I ask him: "Do you know what you have done?" He remains static, head down, no movement to show he has heard the question. Then after a long pause, he looks up. "Yes," is the tentative reply. "Where did you plant the bomb?" "In CP," comes the answer. "Where in CP?"

"Regal cinema," Nisar answers, his voice growing louder and clearer. "Did you know it was a bomb and doing this would kill innocent people?" "Yes." "Why did you do it?" He looks up and says, "For Allah. It’s a jihad for Allah." His eyes seem moist, but it’s not remorse.

He is forthcoming about his background, a Delhiite, not from Azamgarh, he insists. He did his schooling in Delhi and has just graduated in Political Science, Economics and Islamic Studies from Jamia Millia Islamia scoring reasonably well, "three year aggregate marks of 56 per cent", he says proudly.

He had a life beyond jihad, a girl who was more than just a friend, and aspirations for everything that’s usual for a guy of his age—clothes, girls and gadgets.

But, by his own admission, this lifestyle was just a cover to hide his real intent, his real passion – jihad in the name of Allah, for Allah. "I do not miss my girl, my life," he says, a little surprised how the police got to him so soon. "We lead a normal life of a student, beyond suspicion," he says, adding that he believed he would never be caught. "I have no criminal history."

|

Jihad was like a part-time activity that he pursued with utmost seriousness. Nisar used to meet a set of like-minded friends in college and outside to discuss the need for jihad, nature of jihad, to take revenge for atrocities and insults heaped on Muslims. "It is difficult to be a Muslim in India," Nisar says without elaboration.

He never thought, however, that he would end up being a jihadi till about four years ago when he first met Atif at his cousin Shatab’s house (Atif was killed in the September 19, 2008 encounter).

Atif became friend, philosopher and guide to Shakeel, Nisar, Rehman and others in the gang. The Delhi Police calls him the mastermind of the Delhi serial blasts.

They would often hang out together. "We loved to hear Atif talk about jihad," recollects Nisar, talking of his early association with Atif. Initially, Atif would come with Shatab to meet Nisar; later he started coming on his own.

"It was Atif who told me that only a few privileged get to wage jihad for Allah," recounts Nisar. "He would talk for hours about jihad. He was passionate about it and infused the same in me."

Nisar says it took a while for him to be completely indoctrinated. Atif prescribed him a reading list of Urdu literature, mostly about the valiant fight of a jihadi against the enemies of Islam. Nisar makes a special mention of the book Maidan Pukarte Hai, about the struggle of Afghanistan’s Muslims against the Soviet occupation in the 1980s.

The book had a profound impact on him. "The book says that Allah helps a true jihadi, always. And I believe it," he asserts. Nisar insists on narrating an episode from this book about an unarmed jihadi who was surrounded by Russian tanks in the middle of a desert in Afghanistan.

In a desperate bid to save his life, the jihadi threw a fistful of sand he picked up from the ground at the tanks. The sand became a powerful explosive and ripped the Russian tanks apart. "Allah does miracles to save a true jihadi, that’s true," Nisar says, his gaze unblinking, believing every word of this fantastic fairy tale.

He remembers that for many months Atif was judging his will and determination and courage to be a jihadi. "For many years Atif did not tell his real intent, the real task for me. He wanted to make sure I could do it," says Nisar, "I always knew I had the fire for jihad."

The first time Atif actually defined what he meant by jihad was when he inadvertently mentioned how he placed a bomb at the Sankatmochan Temple in Varanasi a couple of years ago. Atif told Nisar in graphic detail how he placed the bomb near a tree in the temple premises where four couples were getting married.

"It gave me a jolt," says Nisar. "Atif was killing people." But then Atif showed him a larger reason for all this bloodshed. " ‘Sometimes you have to adopt evil to prevent a bigger one,’ he told me. ‘It’s not for me or you; it’s for Allah.’ "

Nisar got his first chance to establish his credentials to his immediate group as a true jihadi. He was part of an entourage of 12 sent to plant bombs at Ahmedabad. He did it with no fuss and great success.

"After this, we began to meet more often," said Nisar, "eager to do more jihad. I was particularly close to Atif, Zia and Shatab. Atif liked me; he was impressed by my knowledge of Delhi."

The next opportunity came on September 13. "Atif was worried about our safety that day." Nisar gives a reason for it. "He did not allow us to carry any identity proof, not even a mobile phone." That was not for your safety but his own, Nisar was told. "Did Atif use me in the name of Allah?"

Nisar thinks aloud, "He did not call me even once after the blasts; he did not insist that I attend the customary congregation at L-18 (the module’s hideout) after the blasts."

By now, Nisar is restless. "What will they do with me?" he asks, meaning the police. I remind him: "Do you realise how dangerous you have become?" His eyes flood with tears and he looks up at the ceiling.

"Have you thought about your parents, what would they be going through?" He cries silently. He is perhaps the only one who is feeling the shock and realisation of what he has done. Maybe Nisar is not as hardened a jihadi as he would like to project.

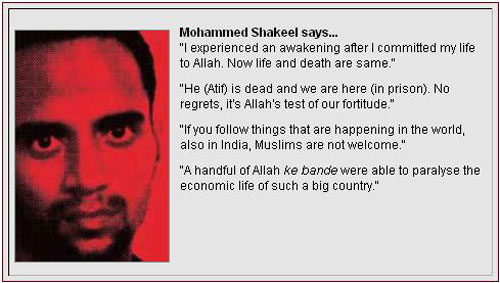

Mohammed Shakeel, 26

A final year student of economics at Jamia Millia Islamia, accused of planting bombs in Ahmedabad and Delhi’s Karol Bagh.

With his face covered, Shakeel is waiting to be paraded in front of the cameras at a press conference by the south Delhi police. A member of his family is with him, so are a few friends who risked meeting him. His face is covered.

"Tell me about yourself," I ask. "I’ve already done that many times to the cops," he says, dismissing the question. Correcting his tone, he says, almost apologetically, "Sir, ask what you want to know, I am an open book, by Allah’s grace."

He goes on to tell me that he has love for life, and wants to enjoy it to fullest. But, it should be a respectable life. "If you follow things that are happening in the world, also in India, Muslims are not welcome."

There are two options, live a life full of contempt, get insulted and abused, or protest in the name of Allah. "I decided to do the latter because had it been only for me it would have not mattered, it’s the name of Allah that they want to soil, and that is not acceptable."

Atif was the man behind his indoctrination as well. "I experienced in me an awakening after I committed my life to Allah. Now nothing scares me, life and death are same," says Shakeel.

|

He has no qualms in acknowledging that he planted a bomb in Ahmedabad. "I planted the parcel in Mani Nagar," he says. A regular at Atif’s hideout, Shakeel lists the people who went with him to Ahmedabad: Nisar’s cousin Shatab, Sajid and Khalid, all on the run, Zia-ur Rehman and Atif.

They were frequent visitors at Atif’s house. "This association was the most passionate phase for our life, nothing mattered, there was no ego, we can do anything for Allah."

Shakeel is believed to be second-in-command after Atif, so it comes as no surprise that he accompanied Atif to Ghaffar Market to plant the bombs.

"We’re all equals in the jihad for Allah, but I was associated longer with the Allah ke bande (men of God). He was happy with the way things were happening. A handful of Allah ke bande were able to paralyse the economic life of such a big country by targeting metros and nothing much could be done about it. We gave back what we were getting from them," Shakeel says.

But like Nisar, he is also puzzled at being caught so easily. "Atif used to say no one can touch us, we are for Allah," he recollects. "He is dead, we are here, no regrets, it’s Allah’s test of our fortitude."

The police have proof. "They have seized a bucket in which we kept barood (explosive) and plastic tape, timer watches and the bags we used," he says anxiously.

He expresses no regret for having killed innocent people. He is clearly no leader, merely a follower, a novice who is yet to come to terms with the true meaning of jihad but dangerous nonetheless.

He is one of those who have no qualms about being a terrorist. "As I told you there is nothing to hide. We are not thieves," he says. That makes him even more dangerous.

Source: India Today